Building Blocks: Addressing Denver’s Housing Affordability Crisis

Among the most universally agreed-upon approaches for increasing rental housing affordability is increasing rental housing supply. A recent study by CoStar underscores this point: in American cities where rental housing supply increased by 3% in a given year, average rents fell by 2-3%. Conversely, cities with no year-over-year increase in supply saw rents climb by 2-4%.

Increasing rental housing supply is, of course, easier said than done and one of the key elements, the ability to attract investment capital, is often given short shrift in policy debates – with disastrous consequences for the cause of housing affordability.

CAPITAL CALLS

Increasing rental housing supply requires two parallel efforts: constructing new homes and preserving existing stock. Both are indispensable, but neither is cheap.

Renovating existing properties is a necessary but expensive endeavor. Time and wear inevitably take their toll on buildings: roofs leak, plumbing corrodes, and interiors age. Renovations, depending on scope, typically cost anywhere from $30,000 to $60,000 per unit. These costs are unavoidable, as failing to maintain existing housing stock merely accelerates its decline.

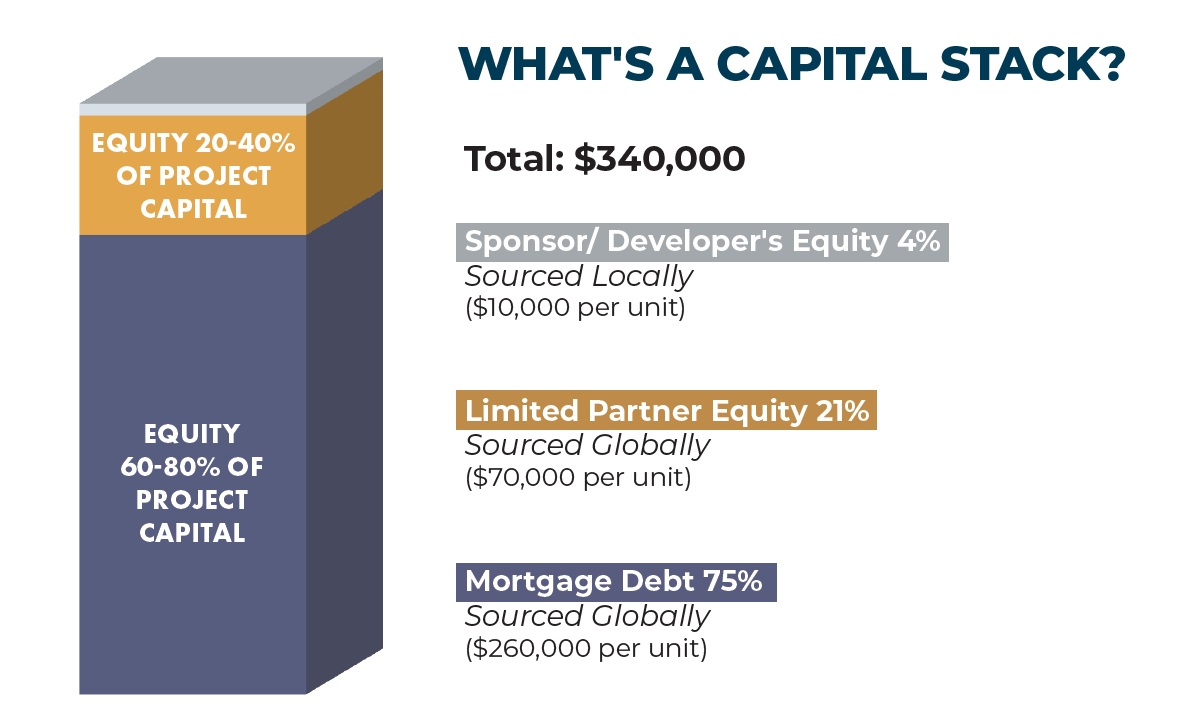

Building new housing, however, makes the task of renovating look like a bargain. In the Denver metro area, the cost of constructing a modest, four-story apartment building typically exceeds $340,000 per unit. To house just 100 families, a developer needs to attract at least $34 million in capital—a daunting figure that underscores the challenge of meeting the city’s needs.

THE FINANCING CHALLENGE

Understanding how developers finance these projects is critical to crafting housing affordability policies that work. Building the complex, multi-layered financing arrangement, known as a “capital stack,” involves two main components: debt and equity.

Debt, primarily sourced from banks or other institutional lenders, usually accounts for about 75% of the capital stack. For a typical new apartment in the Denver metro area, this means lenders cover roughly $260,000 of the $340,000 per-unit cost. The remaining 25%, or $80,000 per apartment, comes from equity capital provided by investors.

Contrary to popular belief, the developer’s financial contribution is modest. Developers can typically provide only 5-15% of the equity, or roughly $10,000 per unit. The rest of the equity—$70,000 per unit—comes from outside investors.

Consequently, 96% of the funds required to build a new apartment in Denver come from external sources, including lenders and investors. For that capital, developers must look beyond Denver’s borders to the global capital markets.

COMPETING IN GLOBAL MARKETPLACE

Investment capital is famously mobile. It flows where the risks are manageable, and the rewards are enticing. Capital for real estate investments is no exception.

CBRE Analytics reported that global real estate investment flows reached a staggering $1.62 trillion in the second quarter of 2022 alone. But capital is fickle. By the fourth quarter of 2023, those flows had plummeted to $650 billion. Investors, spooked by rising interest rates and geopolitical uncertainty, pivoted to safer or more lucrative asset classes.

Between June 2023 and June 2024, $341 billion flowed into US commercial real estate, with $92.9 billion directed toward apartments. Denver captured just 1% of the national total.

To attract the capital necessary to maintain and expand its rental housing, Denver must be viewed as a good bet by global capital providers. But even capital providers for whom Colorado real estate investments should be a slam dunk hesitate to make their money available for Colorado rental housing investments.

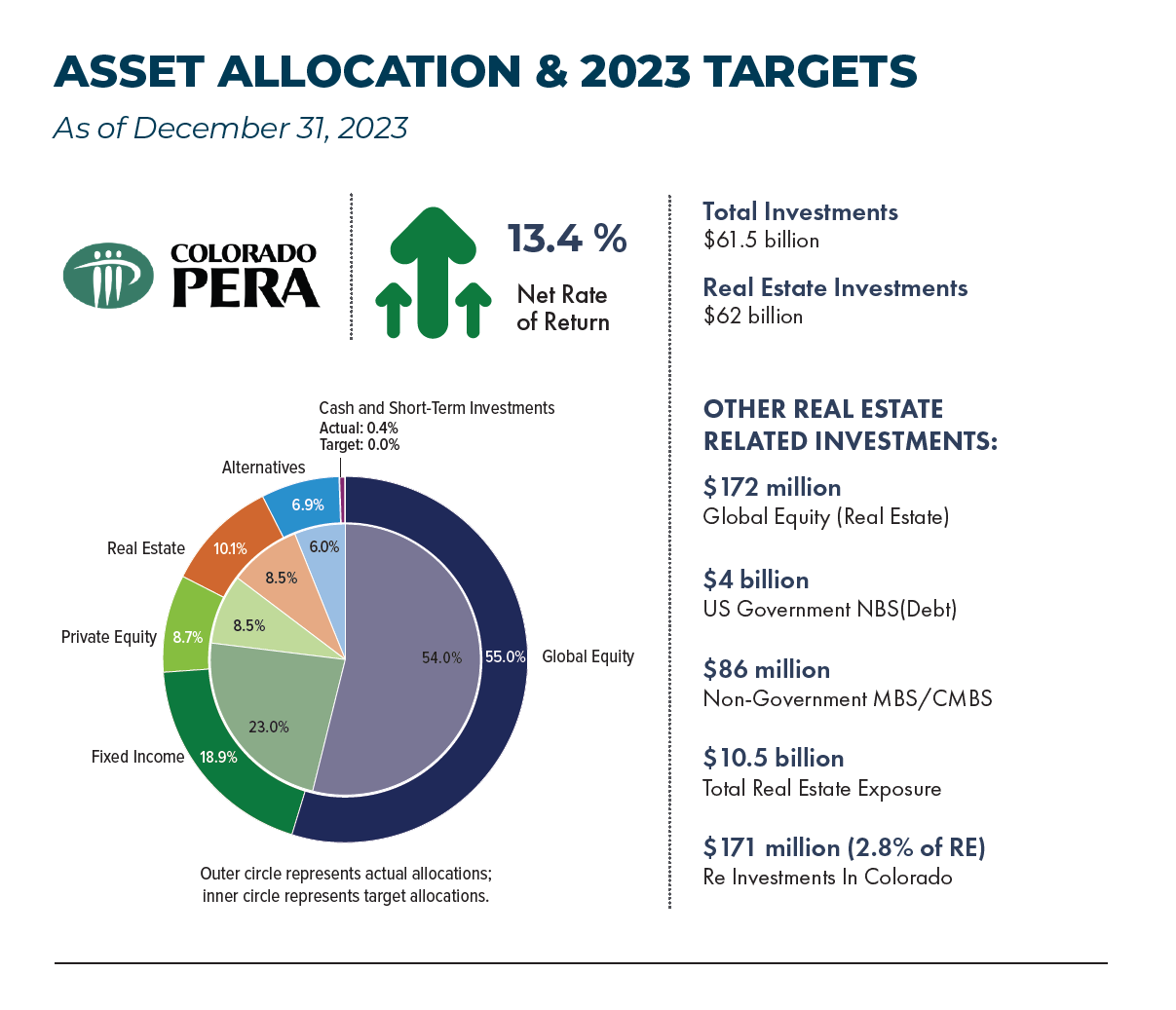

Consider Colorado’s Public Employee’s Retirement Association (PERA), a pension fund that manages $61.5 billion in investments for Colorado retirees. Under PERA’s well-publicized

commitment to investing in Colorado based companies, partnerships, and assets, the pension fund provides much needed investment capital to the communities in which many of PERA’s

retirees live.

It is telling, then, that despite its commitment to local investments, PERA sends 97.2% of its $10.5 billion in real estate-related capital outside of Colorado, according to the pension fund’s most recent annual report.

This reluctance is not unique to PERA. Rather, it reflects a broader caution among investors. Capital flows to opportunities where the rewards justify the risks. Unfortunately, Colorado’s

policy environment often tips the scales in the wrong direction.

THE POLICY PROBLEM

Several factors contribute to hesitancy of capital to flow towards Colorado rental housing investments. Regulatory uncertainty looms large, and a patchwork of local ordinances

and frequently changing housing laws create an unpredictable environment for developers and housing providers.

The prospect of rent control is another major deterrent. While intended to protect tenants, academic research has demonstrated time and time again that rent control policies drive risks up, returns down, and capital away.

Finally, increases in regulatory burden add to the cost of doing business. Developers of new housing especially must navigate a maze of permitting processes, zoning restrictions, and

impact fees. Each additional hurdle makes Colorado a less attractive destination for capital.

By increasing the risk of investing in Colorado’s housing market, many affordable housing policy remedies end up reducing the pool of capital willing to back local projects - with predictable and frustrating results.

The riskier development projects appear, the higher the returns developers must offer to attract capital to their projects. In a bitter irony for cost-burdened residents, the new

projects that could ease rents get put on hold until, driven by scarcity, rents rise to meet the heightened risk. Policies designed to help tenants can end up harming them instead.

INCREASING HOUSING AFFORDABILITY

If Denver is to address its housing affordability crisis, it must position itself as a competitive destination for global capital. This requires creating a stable and predictable policy environment.

State and local governments should commit to regulatory consistency. Clear, long-term rules reduce uncertainty and make the market more attractive to institutional investors like PERA. Policymakers should also carefully evaluate the unintended consequences of rent control and other tenant protections. While well-intentioned, these measures often drive away investment capital.

The stakes could not be higher. If Denver fails to attract the capital necessary to expand its housing supply, it risks deepening the affordability crisis that has already left too many residents struggling to find a place to call home.

Denver must compete—and win— in the global marketplace for capital. Achieving this will require thoughtful policy and a commitment to creating an environment where both residents and capital can find a home.